It has been many months since I have posted any original essays here. I could make the excuse that I’ve been too busy to write, or that I can’t think of anything to write about. The truth is that like most people, I have had the time to do pretty much whatever I choose, but have chosen to spend it in other ways. As for having topics to write about, there is an abundance of thought running through my mind each day, and I have imagined a hundred blogs in the months that have passed. So why haven’t I written?

If I were to answer that question honestly, I would have to say that I’ve been avoiding the inevitable. My recent philosophical and spiritual journeys have carried me far beyond the familiar territory of the evangelical Christian village where I have lived most of my life. As I’ve pondered the sights along the way, and stopped in awe to take in the unfamiliar, expansive landscapes, I’ve come to understand the richness and diversity of the human experience in the vastness of time and place. Mind you, this does not diminish the significance of my tiny village, my place of origin. Rather, it establishes the context of my former habitat, and reveals to me the larger canvas upon which is painted the masterpiece of human existence. I have become aware of my own myopia, and the dramatic change in perspective requires time for the eyes to adjust. And so for the last several months, my focus has been in flux as I have awaited a moment of clarity. These moments are coming now as night and fog give way to new vistas and overlooks.

So what is inevitable about this? Well with changing perspectives come changing beliefs. And it is inevitable that new ways of thinking will at some point either fortify or raze former building blocks of thought. Without the benefit of the larger context, the myopic view of truth may seem sufficient, and may be all that is required to be a faithful citizen of one’s village. But with the larger canvas in view, old assumptions inevitably must be examined in light of new information and evidence. Previous assumptions based on universal truths will prove to be useful in the larger context. Assumptions which thrive on narrower view, to the exclusion of the larger canvas, may be shown to be less meaningful or relevant than previously believed. One example of this which has been on my mind of late is the nature and role of scripture.

With few exceptions, the circle of people with whom I have closely associated for the past 35 years would describe themselves as evangelical, or “born again” Christians. This particular worldview has been a persistent thread running through my life. Among the non-negotiable doctrines of the evangelical Christian church is a view of the Christian scriptures, the Bible, as the literal, inspired, inerrant word of God. Many, many books have been written examining this treatise, and I have no intention of either supporting nor critiquing this central idea. I’m simply not qualified. The truth is, however, that something like 30% of American evangelicals believe in some variety of biblical literal inerrancy, and they do so despite overwhelming evidence that their view of the origin and context of scripture bears little resemblance to its true origin and context. Far from being a neatly bound, annotated, gilded-edged, harmonized love letter from God, the Christian scriptures are a not-so neat, often ambiguous, rough-around-the-edges, often self contradictory collection of writings which have survived nearly two millennia in the hands of various human beings, all of whom had an agenda in mind, however magnanimous. To be sure, it is a beautiful, inspiring, and often transformative work. To me, the prevalent literal, reductionist view of scripture does harm to the bible and degrades its value. I find it much more useful to view the Bible as art. And this requires one to take a less myopic view, to take a few steps back and view the canvas as a whole.

Consider for a moment an art professor in a college art class. His fifteen young students are sitting at the perimeter of the studio. At the center of the studio, atop a low platform, reclines a model lightly draped in white satin. Now each person reading this will have already formed a picture of this scene in their mind. Some may have envisioned a dark, beautiful nude female form, others a statuesque, modestly attired greek-god type. In any case, the students in the studio have the benefit of actually seeing the model there in front of them, and they have been charged with interpreting this form through whatever media they wish. Now it can be said with some certainty that this is not the first class to view the model and artistically interpret it. In fact, this prestigious university may have held similar art studio sessions two centuries prior, with students gathered around a model, brush in hand. It is a true statement that each student’s interpretation of the very model they see in front of them will be different than every other student’s work. In fact, it would be safe to say that the work of this class as a whole will be very different than the work of a similar class of students two centuries ago. Why? We intuitively understand the answer: each student is painting in the context of their own experience, bias, and worldview. If the model is a nude woman, some students will take liberty to paint the naughty bits a bit more modestly. Others will paint the figure more true to form, or their work will be more impressionist or abstract. It is safe to say that none of the paintings will render the model with the same true, honest result that a photograph would, nor should they.

So why is this the case? Could it be that the artists work is not intended to render with the exact duplication of a photograph? Wouldn’t the artist wish to put some of himself into his work, to allow the viewer some space to experience the work through their own interpretation? And more importantly, is the painting less valid as a representation of the subject than a photograph would be?

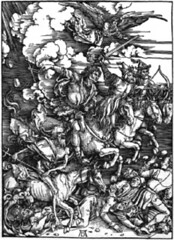

It is clear to me that if God inspired scripture, he used artists, not photographers, to create the picture. The Bible consists of sixty six writings by forty authors over a period of 1,500 years. And yet apologists for biblical inerrancy and literalism will offer any explanation, no matter how ill-supported, to insist on their assertion that we are looking at a photograph rather than an ancient human interpretation, however inspired. All of the artists of scripture were influenced by their context: their drive for ethnic or religious survival, their deeply held values and ethics, and their own personal or cultural world view. Do these influences invalidate the value of the scriptures? To the contrary. For me, the diversity of viewpoints, of vistas found within scripture only serves to enrich the value of these sacred works. The literalists’ reduction of all scripture to direct, God-breathed tenets at best creates a wealth of contextual conundrums, and at worst calls into question the nature of a God who would dictate such a book. It’s safer to assume that God, such that he exists, alone is inerrant, and any human effort to describe that reality will naturally fall short of that highest status. Yet these descriptions, human as they are, still provide a spectacular view and tell us much about the human condition and humankind’s aspirations to become something greater that we are or ever have been.

As Robert Price wrote in his book The Reason Driven Life, “An ambiguous, inerrant scripture is no better than an errant one”. This is to say that a literal, inerrant interpretation of the bible creates ambiguities and conflicts which are unnecessary, and which do the Bible a great injustice. This is as if an art critic, intent on learning everything he could about the aforementioned model, set forth to reduce the students’ art work to their barest elements. He would analyze the paint chips, learn everything about each artist, and attempt to “harmonize” the differences between each piece in an attempt to establish a composite picture which accurately describes the subject in photographic detail. This is an absurdity, since each piece was intended to interpret the subject on its own merit. And yet this is exactly how scripture has been treated by literal reductionists ever since the reformation began.

And so my journey continues. I’m relieved to find that what I thought was a map for my journey is instead an inspiring, insightful travel guide. I’ve learned that the map is the territory, and a rich and awe-inspiring territory it is.